The present column is devoted to Geometry/Topology.

I Six new problems – solutions solicited

Solutions will appear in a subsequent issue.

252

Prove that the space of unordered couples of distinct points of a circle is the (open) Möbius band. More formally, consider

and the equivalence relation on this space ; prove that the quotient topological space is the (open) Möbius band.

Costante Bellettini (Department of Mathematics, University College London, UK)

253

In the Euclidean plane, let and be two concentric circles of radius respectively and , with . Show that the locus of points such that the polar line of with respect to is tangent to is a circle of radius .

Acknowledgement

I want to thank the professors who guided me in the first part of my career for giving me the ideas for these problems.

Paola Bonacini (Mathematics and Computer Science Department, University of Catania, Italy)

254

Let be a connected open subset of Euclidean space, and suppose that the following conditions hold:

Every smooth irrotational vector field on admits a potential (i.e., it is the gradient of a smooth function).

The closure of is a smooth compact submanifold of (of course, with non-empty boundary).

Show that is simply connected. Does this conclusion hold even if we drop condition (2) on ?

Roberto Frigerio (Dipartimento di Matematica, Università di Pisa, Italy)

255

A regulus is a surface in that is formed as follows: We consider pairwise skew lines and take the union of all lines that intersect each of , , and . Prove that, for every regulus , there exists an irreducible polynomial of degree two that vanishes on .

Adam Sheffer (Department of Mathematics, Baruch College, City University of New York, NY, USA)

256

(Enumerative Geometry). How many lines pass through generic lines in a -dimensional complex projective space ?

Mohammad F. Tehrani (Department of Mathematics, University of Iowa, USA)

257

I learned about the following problem from Shmuel Weinberger. It can be viewed as a topological analogue of Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem.

(a) A group of friends have decided to spend their summer cottaging together on an undeveloped island, which happens to be a perfect copy of the closed 2-disk . Their first task is to decide where on this island to build their cabin. Being democratically-minded, the friends decide to vote on the question. Each friend chooses his or her favourite point on . The friends want a function that will take as input their votes, and give as output a suitable point on to build. They believe, to be reasonable and fair, their “choice” function should have the following properties:

(Continuity) It should be continuous as a function . This means, if one friend changes their vote by a small amount, the output will change only a small amount.

(Symmetry) The friends should be indistinguishable from each other. If two friends swap votes, the final choice should be unaffected.

(Unanimity) If all friends chose the same point , then should be the final choice.

For which values of does such a choice function exist?

(b) The friends’ second task is to decide where along the shoreline of the island they will build their dock. The shoreline happens to be a perfect copy of the circle . Again, they decide to take the problem to a vote. For which values of does a continuous, symmetric, and unanimous choice function exist?

These are special cases of the following general problem in topological social choice theory: given a topological space , for what values of does admit a social choice function that is continuous, symmetric, and unanimous? In other words, when is there a function satisfying

is continuous,

is independent of the ordering of , and

for all ?

Jenny Wilson (Department of Mathematics, University of Michigan, USA)

II Open problem

Embeddings of contact domains

by Yakov Eliashberg (Department of Mathematics, Stanford University, USA)

One of the cornerstones of symplectic topology, Gromov’s non-squeezing theorem, see [6 M. Gromov, Pseudo holomorphic curves in symplectic manifolds. Invent. Math. 82, 307–347 (1985) ], asserts that for the ball of radius in the standard symplectic space does not admit a symplectic embedding into the domain

while there is no volume constraints to do that. Since that time, the theory of symplectic embedding has made a lot of progress (see F. Schlenk’s survey [8 F. Schlenk, Symplectic embedding problems, old and new. Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.) 55, 139–182 (2018) ] for recent results).

The (non-)embedding results in contact geometry, which is an odd-dimensional analogue of symplectic geometry, are rarer; below, we discuss a few open problems.

Recall that a contact structure on an -dimensional manifold is a completely non-integrable hyperplane field. If is defined by a Pfaffian equation for a differential -form (and such a form can always be found locally, and if is co-orientable even globally) then the complete non-integrability can be expressed by the condition that is a non-vanishing -form on .

In this set of problems, we will restrict our attention to domains in the contact manifold , , endowed with the contact structure

Given a bounded domain , we set

and refer to as a quantized domain . We say that a domain admits a contact embedding into a domain if there is a contact isotopy , starting with the inclusion such that . Note that any Hamiltonian isotopy which moves into lifts to a contact isotopy moving into . Hence we will refer to the problem of contact embeddings between the domains and as a quantized version of the corresponding symplectic embedding problem of to .

Denote by the -dimensional open ball of radius and by the polydisk , where . It was shown in [3 Y. Eliashberg, S. S. Kim and L. Polterovich, Geometry of contact transformations and domains: orderability versus squeezing. Geom. Topol. 10, 1635–1747 (2006) ] that if for any integer , then does not admit a contact embedding into . Another theorem from [3 Y. Eliashberg, S. S. Kim and L. Polterovich, Geometry of contact transformations and domains: orderability versus squeezing. Geom. Topol. 10, 1635–1747 (2006) ] states that if , then admits a contact embedding into for any . The former result was improved in [2 S.-F. Chiu, Nonsqueezing property of contact balls. Duke Math. J. 166, 605–655 (2017) , 5 M. Fraser, Contact non-squeezing at large scale in ℝ2n×S1. Internat. J. Math. 27, 1650107 (2016) ] to show that for any with there is no contact embedding of into . Recall that Gromov’s symplectic width of a domain can be defined as the supremum of such that can be symplectically embedded into the domain . The above results can be slightly generalized to the following statement, see [3 Y. Eliashberg, S. S. Kim and L. Polterovich, Geometry of contact transformations and domains: orderability versus squeezing. Geom. Topol. 10, 1635–1747 (2006) ].

If, for two domains , we have

then the quantized domain does not admit a contact embedding into .

Very little is known about embeddings of contact domains beyond the above results. Let us formulate a couple of concrete problems concerning quantized versions of some relatively old embedding results in symplectic topology. As we already mentioned above, many new obstructions to symplectic embeddings were found in recent years. It is unknown whether any of them hold in the quantized versions.

258*

Contact packing problem. Suppose that . Is there a maximal number of quantized balls which admit a contact packing into ? And if the answer is “yes”, then what is this number?

Here we say that admits a contact packing by quantized balls if the disjoint union

admits a contact embedding into . Note that the corresponding symplectic packing problem was intensively studied beginning with the seminal paper by Gromov [6 M. Gromov, Pseudo holomorphic curves in symplectic manifolds. Invent. Math. 82, 307–347 (1985) ], where he proved that the packing of the ball with 2 disjoint balls is possible if and only if . For , the problem was significantly advanced by D. McDuff and L. Polterovich in [7 D. McDuff and L. Polterovich, Symplectic packings and algebraic geometry. Invent. Math. 115, 405–434 (1994) ], and then completely solved by P. Biran in [1 P. Biran, Symplectic packing in dimension 4. Geom. Funct. Anal. 7, 420–437 (1997) ]. In the contact case, Problem 258* is completely open.

259*

Rotating quantized polydisks. For , consider the standard contact inclusion . Let , be the corresponding contact inclusion , and consider the contactomorphism . When are the embeddings contact isotopic?

Note that a theorem of Floer–Hofer–Wysocki, see [4 A. Floer, H. Hofer and K. Wysocki, Applications of symplectic homology. I. Math. Z. 217, 577–606 (1994) ], states that when the symplectic embeddings are not symplectically isotopic.

III Solutions

245

We consider a setting where there is a set of candidates

and a set of voters . Each voter ranks all candidates from the most preferred one to the least preferred one; we write if voter prefers candidate to candidate . A collection of all voters’ rankings is called a preference profile. We say that a preference profile is single-peaked if there is a total order on the candidates (called the axis) such that for each voter the following holds: if ’s most preferred candidate is and or , then . That is, each ranking has a single “peak”, and then “declines” in either direction from that peak.

(i) In general, if we aggregate voters’ preferences over candidates, the resulting majority relation may have cycles: e.g., if , and , then a strict majority (2 out of 3) voters prefer to , a strict majority prefer to , yet a strict majority prefer to . Argue that this cannot happen if the preference profile is single-peaked. That is, prove that if a profile is single-peaked, a strict majority of voters prefer to , and a strict majority of voters prefer to , then a strict majority of voters prefer to .

(ii) Suppose that is odd and voters’ preferences are known to be single-peaked with respect to an axis . Consider the following voting rule: we ask each voter to report their top candidate , find a median voter , i.e.,

and output . Argue that under this voting rule no voter can benefit from voting dishonestly, if a voter reports some candidate instead of , this either does not change the outcome or results in an outcome that likes less than the outcome of the truthful voting.

(iii) We say that a preference profile is 1D-Euclidean if each candidate and each voter can be associated with a point in so that the preferences are determined by distances, i.e., there is an embedding such that for all and , we have if and only if . Argue that a 1D-Euclidean profile is necessarily single-peaked. Show that the converse is not true, i.e., there exists a single-peaked profile that is not 1D-Euclidean.

(iv) Let be a single-peaked profile, and let be the set of candidates ranked last by at least one voter. Prove that .

(v) Consider an axis . Prove that there are exactly distinct votes that are single-peaked with respect to this axis. Explain how to sample from the uniform distribution over these votes.

These problems are based on references [12 H. Moulin, Axioms of Cooperative Decision Making. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1991) ] (parts (i) and (ii)), [10 C. H. Coombs. Psychological scaling without a unit of measurement. Psychological Review 57, 145 (1950) ] (part (iii)) and [9 V. Conitzer, Eliciting single-peaked preferences using comparison queries. J. Artificial Intelligence Res. 35, 161–191 (2009) , 13 T. Walsh, Generating single peaked votes. arXiv:1503.02766 (2015) ] (part (v)); part (iv) is folklore. See also the survey [11 E. Elkind, M. Lackner and D. Peters. Structured preferences. In Trends in Computational Social Choice, edited by U. Endriss, Chapter 10, AI Access, 187–207 (2017) ].

Edith Elkind (University of Oxford, UK)

Solution by the proposer

(i) We can restrict the voters’ preferences to the set ; the reader can check that a restriction of a single-peaked profile to a subset of candidates remains single-peaked. We consider three cases depending on how , and are ordered by the axis .

or . Then all voters who prefer over have as their top choice and hence prefer to .

or . All voters who prefer over have as their top choice and hence prefer to ; therefore, these voters are in minority.

or . This is impossible: all voters who prefer to have as their top choice, so we have a strict majority preferring over , a contradiction.

(ii) Suppose the winner under truthful voting is . Consider a voter . If , then cannot improve the outcome by lying. So suppose (the case is symmetric). If reports or some candidate with , this does not change what the top choice of the median voter is, and hence does not change the outcome. If reports a candidate with , then the median voter may shift to the right, i.e., further away from ’s true top choice; as ’s preferences are single-peaked, this does not improve the outcome from her perspective.

(iii) Ordering the candidates by their position, i.e., placing before on the axis if results in an axis witnessing that the input profile is single-peaked. To show that the converse is not true, consider the following four votes:

This profile is single-peaked on . Now, suppose for contradiction that it is 1D-Euclidean, i.e., it admits an embedding . Consider the positions of the four voters . Assume without loss of generality that . Then we have

(as voters 1 and 3 prefer to ) and

(as voters 2 and 4 prefer to ). But now consider the point . Voters 1 and 2 have to be on one side of this point and voters 3 and 4 have to be on the other side of this point, because of their preferences over vs. . But this is clearly impossible!

(iv) Assume without loss of generality that is single-peaked with respect to the axis . Clearly, may contain a vote that ranks last or a vote that ranks last. But it cannot contain a vote that ranks some with last: if the top candidate in that vote is a with , then this voter prefers to , and if the top candidate in that vote is a with , then this voter prefers to .

(v) Induction. For , we have orders, i.e., and . Now suppose the claim has been proved for all . A vote that is single-peaked on may have in the last position, with candidates in top positions forming a single-peaked vote with respect to ( options) or it may have in the last position, with candidates in top positions forming a single-peaked vote with respect to ( options). For sampling, we can build the vote bottom-up. At the first step, we fill the last position with or , with probability each. Once positions have been filled, , the not-yet-ranked candidates form a contiguous segment of the axis. We then fill position from the bottom with or , with equal probability. This sampling is uniform, because the probability of generating a specific ranking is exactly : we make choice, and with probability each choice is consistent with the target ranking.

246

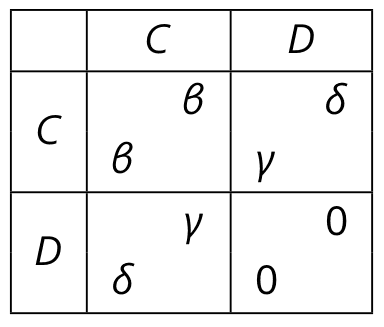

Consider a standard prisoners’ dilemma game described by the following strategic form, with :

Assume that any given agent either plays or and that agents reproduce at a rate determined by their payoff from the strategic form of the game plus a constant . Suppose that members of an infinite population are assorted into finite groups of size . Let denote the proportion of agents playing strategy (“altruists”) in the population as a whole and denote the proportion of agents playing in group . We assume that currently .

The process of assortment is abstract, but we assume that it has finite expectation and variance . Members within each group are then randomly paired off to play one iteration of the prisoners’ dilemma against another member of their group. All agents then return to the overall population.

Find a condition relating , , , , and under which the proportion of altruists in the overall population rises after a round of play.

Now interpret this game as one where each player can confer a benefit upon the other player by individually incurring a cost , with , so that , and . Prove that, as long as (i) there is some positive assortment in group formation and (ii) the ratio is low enough, then the proportion of altruists in the overall population will rise after a round of play.

Richard Povey (Hertford College and St Hilda’s College, University of Oxford, UK)

Solution by the proposer

(a) We can firstly see that the number of altruists (type ) and non-altruists (type ) in group after a round of play will be given by

Summing these two equalities yields

Given an infinite population and hence an infinite number of groups, the new proportion of altruists in the overall population will be

Substituting in and gives us

Assuming is high enough to make the denominator positive, it then follows that

After some further rearrangement, we can derive the following:

Since the right-hand side of (1) must be strictly between and , this has the intuitive interpretation that the inter-group variance must be sufficiently high relative to the intra-group variance1This is the variance of the Bernoulli variable which takes a value of of a single individual drawn from the population is an altruist and otherwise, which is . so that, although altruists do less well relative to non-altruists within each group, the concentration of altruists together within particular groups is sufficiently strong to confer enough of an evolutionary advantage to offset this and to enable altruists to do better evolutionarily than non-altruists in the overall population.2This result was first proved in a general evolutionary context by George R. Price [16 G. R. Price, Selection and covariance, Nature 227, 520–521 (1970) , 17 G. R. Price, Extension of covariance selection mathematics, Ann. Human Genetics 35, 485–490 (1972) ].

(b) In the case where , and , condition (1) can be rearranged to give

With random assortment, would be equal to where , the number of altruists in group would have a binomial distribution: . Therefore

With perfect positive correlation between group members, we would get

With some positive assortment generating positive covariance between group members, we may therefore without loss of generality suppose that

where . Plugging this into (2) and simplifying, we get . So we can see that for any there always exists a value of low enough for altruists to expand as a proportion of the overall population.3The literature on this model has further established the results that multiple periods of isolation in finite groups acts to amplify inter-group variance, so that even with random assortment into groups altruism can evolve [14 B. Cooper and C. Wallace, Group selection and the evolution of altruism. Oxford Economic Papers 56, 307–330 (2004) ]. It has also been found that use of punishment strategies in dynamic interactions can act to weaken this group selection mechanism [15 R. Povey, Punishment and the potency of group selection, J. Evolutionary Economics 24 (2014) ]. For an accessible book-length treatment of the topic of group selection in the biological and social sciences, see [18 E. Sober and D. S. Wilson, Unto Others, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1999) ].

247

Consider a village consisting of n farmers who live along a circle of length . The farmers live at positions . Each of them is friends with the person to the left and right of them, and each friendship has capacity where is a non-negative integer. At the end of the year, each farmer does either well (her wealth is dollars) or not well (her wealth is dollars) with equal probability. Farmers’ wealth realizations are independent of each other. Hence, for a large circle the share of farmers in each state is on average .

The farmers share risk by transferring money to their direct neighbors. The goal of risk-sharing is to create as many farmers with OK wealth (0 dollars) as possible. Transfers have to be in integer dollars and cannot exceed the capacity of each link (which is ).

A few examples with a village of size serve to illustrate risk-sharing.

Consider the case where farmers 1 to 4 have wealth

In that case, we can share risk completely with farmer sending a dollar to agent and farmer sending a dollar to farmer . This works for any .

Consider the case where farmers to have wealth

In that case, we can share risk completely with farmer sending a dollar to farmer , farmer sending two dollars to farmer and farmer sending one dollar to farmer . In this case, we need . If , we can only share risk among half the people in the village.

Show that for any wealth realization an optimal risk-sharing arrangement can be found as the solution to a maximum flow problem.

Tanya Rosenblat (School of Information and Department of Economics, University of Michigan, USA)

Solution by the proposer

We augment the village graph by adding two auxiliary nodes. The source node is connected to all the farmers with positive wealth () and each of these links has capacity . The sink node is connected to all the farmers with negative wealth () and each of these links also capacity . We now look for the maximum flow from to : this is equal to the number of luck/unlucky farmer pairs who can be matched under the best risk-sharing arrangement.

248

This exercise is a continuation of Problem 247 where we studied risk-sharing among farmers who live on a circle village and are friends with their direct neighbors to the left and right with friendships of a certain capacity. Assume that for any realization of wealth levels the best possible risk-sharing arrangement is implemented and denote the expected share of unmatched farmers with . Show that as .

Tanya Rosenblat (School of Information and Department of Economics, University of Michigan, USA)

Solution by the proposer

The solution proceeds in two stages. In Problem 247, we already established that the problem can be understood as a maximum flow problem. We first formulate a particular algorithm that implements this flow. We then use this algorithm to express in closed form.

Risk-sharing as a Maximum Flow Problem

We next describe a matching algorithm which is to run for rounds. The claim is that this algorithm implements the maximum flow in the augmented graph for any . For the purpose of this algorithm, we call a black agent an agent with positive shock and a white agent an agent with a negative shock.

Step I: Index all agents from to clockwise ( is the neighbor of on a circle). Set the counter to .

Step II: If agents and are of different colors, label them “matched” and move the counter clockwise to . If agent has the same color as agent , then declare agent “unmatched” and move the counter clockwise to agent . Repeat this step until the counter has reached the first agent again.

Step III: Define a new circle by ordering all the unmatched agents on a circle without disturbing the order of the agents. Essentially, this implies that all the matched agents are simply removed from the circle and any gaps are plugged by connected the closest unmatched agents with each other. Repeat steps I and II for this new circle. Repeat this algorithm times.

Lemma 1. The above matching algorithm implements the maximum flow.

Proof. The Ford–Fulkerson algorithm computes the maximum flow by looking for open paths which can carry positive flow and then constructing a graph with augmented capacities in which the next path is found, etc. Once no more open path exists the max flow has been implemented. The above algorithm implements Ford–Fulkerson using a particular order of selecting open paths. Therefore, it implements the max flow.

Closed form solutions. We next prove the following lemma.

Lemma 2. Assume we have a circle of size where the probability that an agent has a neighbor of the same color is . Then the share of unmatched agents after one round of the above algorithm converges to as .

Proof. In each instance of step I of the algorithm, it produces an unmatched agent with probability and a pair of matched agents with probability . The sum of unmatched and matched agents has to be . Therefore the share of unmatched agents converges to

The final step in the proof of the result is to derive the probability that an agent is followed by a same-color agent in round . We know that in round shocks are i.i.d.; therefore . We start by proving a recursive formula for calculating .

Lemma 3. If the sequential probability is in round , then the sequential probability in round satisfies

Proof. Consider an agent on whom the counter rested at some point in the algorithm and who stays unmatched in the current round. This must be because he has a neighbor of the same color (without loss of generality assume both are black). With probability agent is also black and therefore agent will survive into round as well and be of the same color as agent (black). With probability agent is white. In this case agents and can be matched. Matching can continue for the subsequent pairs of agents , , etc.; it will only stop if for any of these pairs agents have the same color. This will happen with probability . To figure out it if this process will stop at a “white pair” or a “black pair” (let’s call it the “blocking pair”) it is crucial to know whether agent , , , etc. (i.e., the agent just prior to the blocking pair) is white or black.

We know that agent is white. What is the probability that agent is the same color (provided is not a blocking pair)? This can only happen if the pair is a black agent followed by a white agent. If it is a white agent followed by a black agent then has a different color from . So the probability of a color change is

Assume that the probability that the agent prior to the blocking pair is of the same color as is . With probability the pair is a blocking pair and with probability the pair is not blocking. In that case agent has a different color from agent with probability . Because of the recursive nature of the problem, the probability that the agent prior to the blocking pair has the same color as is . Therefore we know that

This allows us to calculate as

So we know that the agent prior to the blocking pair is white with probability . The blocking pair is therefore a black blocking pair with probability . Therefore the total probability that the next unmatched agent after agent is of the same color (black in this case) is

We can check that satisfies both the initial condition and the recursive equation 3. This implies that

Finally, note that the share of unmatched agents (for ) can be calculated by taking the product of the share of unmatched agents in each round:

249

In a combinatorial auction there are items for sale to buyers. Each buyer has some valuation function which takes as input a set of items and outputs that bidder’s value for that set. These functions will always be monotone ( for all ), and satisfy .

Definition 1 (Walrasian equilibrium). A price vector and a list of subsets of form a Walrasian equilbrium for if the following two properties hold:

Each .

The sets are disjoint, and .

Prove that a Walrasian equilibrium exists for if and only if there exists an integral4That is, a point such that each . optimum to the following linear program:

Hint. Take the dual, and start from there.

Matt Weinberg (Computer Science, Princeton University, USA)

Solution by the proposer

First, we take the dual of the given LP. We use the dual variable for the constraints involving items, and the dual variable for the constraints involving bidders. Then the dual problem is

Walrasian equilibrium implies integral optimum

Now, assume that a Walrasian equilibrium exists, and let it be and . Then consider the integral solution to the LP that sets for all , and all other variables to . This solution is clearly feasible for the LP, and has objective value equal to .

Consider also the dual solution , with as given in the Walrasian equilibrium. We claim this is a feasible solution to the dual. To see this, observe first that each . Also, because by definition of Walrasian equilibrium, we have that

Therefore, all dual constraints are satisfied, and this is a feasible dual. Moreover, observe that the value of the dual objective is

The last equality follows because each item is in exactly one bundle . So we have proved that if is a Walrasian equilibrium, then there is an integral feasible point for the LP with objective value , and also a feasible dual solution with value . By LP duality, both feasible solutions are in fact optimal. Therefore, there is an integral optimum for the LP.

Integral optimum implies Walrasian equilibrium

Now, assume that the LP has an integral optimum. Observe that for this integral solution, there must exist disjoint sets such that for each , and all other variables are . The LP value for this solution is . Moreover, observe that if any item , we can add to an arbitrary without decreasing (because each is monotone). Therefore, if there is an integral optimum to the LP, there exist disjoint such that and is the optimal solution to the LP.

By Strong LP Duality, there also exists a feasible dual solution such that . We will claim that form a Walrasian equilibrium.

For a proof by contradiction, assume that this is not the case. Then there must be some bidder such that . In particular, this means that there exists some such that . Because is a feasible solution for the dual, we then conclude that

We claim that this contradicts the fact that , since

The first inequality holds because for all , and the inequality is strict for at least one . Therefore, must be a Walrasian equilibrium.

Wrapup

This concludes the proof. We have shown that there is an integral optimum to the LP if and only if a Walrasian equilibrium exists. The solution to this problem is given by Nisan et al. in [24 N. Nisan, T. Roughgarden, É. Tardos and V. V. Vazirani, Algorithmic game theory. Cambridge University Press (2007) , Corollary 11.16]; they cite [22 S. Bikhchandani and J. W. Mamer, Competitive equilibrium in an exchange economy with indivisibilities. J. Econom. Theory 74, 385–413 (1997) , 23 S. Bikhchandani and J. M. Ostroy, The package assignment model. J. Econom. Theory 107, 377–406 (2002) ].

250

Consider a game played on a network and a finite set of players .5For an overview of the literature on network games, see [20 M. O. Jackson and Y. Zenou, Games on networks. In Handbook of Game Theory. Vol. 4, edited by H. P. Young and S. Zamir, Handbooks in Economics, 91–157, Elsevier/North-Holland, Amsterdam (2015) ]. Each node in the network represents a player and edges capture their relationships. We use to represent the adjacency matrix of a undirected graph/network, i.e., . We assume . Thus, is a zero-diagonal, squared and symmetric matrix. Each player, indexed by , chooses an action and obtains the following payoff:

The parameter captures the strength of the direct links between different players. For simplicity, we assume .

A Nash equilibrium is a profile such that, for any ,

In other words, at a Nash equilibrium, there is no profitable deviation for any player choosing .

Let , for all (the transpose of a vector is denoted by ), and the identity matrix. Define the weighted Katz–Bonacich centrality vector as

Here denote the inverse Leontief matrix associated with network , while denote its entry, which is equal to the discounted number of walks from to with decay factor . Let be a vector of s. Then the unweighted Katz–Bonacich centrality vector can be defined as

Show that this network game has a unique Nash equilibrium . Can you link this equilibrium to the Katz–Bonacich centrality vector defined above?

Let denote the sum of actions (total activity) at the unique Nash equilibrium in part 1. Now suppose that you can remove a single node, say , from the network. Which node do you want to remove such that the sum of effort at the new Nash equilibrium is reduced the most? (Note that, after the deletion of node , we remove all the links of node , and the remaining network, denoted by , can be obtained by deleting the -th row and -th column of .)

Mathematically, you need to solve the key player problem6The key player problem has been introduced in [19 C. Ballester, A. Calvó-Armengol and Y. Zenou, Who’s who in networks. Wanted: the key player. Econometrica 74, 1403–1417 (2006) ].

In other words, you want to find a player who, once removed, leads to the highest reduction in total action in the remaining network.

Hint. You may come up with an index for each such that the key player is the one with the highest . This should be expressed using the Katz–Bonacich centrality vector defined above.

Now instead of deleting a single node, we can delete any pair of nodes from the network. Can you identify the key pair, that is, the pair of nodes that, once removed, reduces total activity the most?7For the analysis of group players, see [19 C. Ballester, A. Calvó-Armengol and Y. Zenou, Who’s who in networks. Wanted: the key player. Econometrica 74, 1403–1417 (2006) , 21 Y. Sun, W. Zhao and J. Zhou, Structural interventions in networks. arXiv:2101.12420 (2021) ].

Yves Zenou (Monash University, Australia) and Junjie Zhou (National University of Singapore)

Solution by the proposer

(1) Suppose that is a Nash equilibrium. Then we obtain the following optimality equation for player :

In matrix form,

or

In other words, the Nash equilibrium effort is exactly equal to the unweighted Katz–Bonacich vector.

Note that, under the assumption that , the matrix is invertible, and the inverse matrix has the following infinite sum representation:

For uniqueness, it is obvious.

(2) Before solving it, we first enrich the baseline model by taking into account heterogeneous individual weights ,

The unique equilibrium of this extended model corresponds to the weighted Katz–Bonacich centrality

or, equivalently, for each :

where gives the number of walks of length from to in the network and is the weighted Katz–Bonacich centrality of player .

The aggregate equilibrium action is then equal to

Intuitively, when increases by 1 unit, , each player ’s equilibrium effort increases by , and the total equilibrium action increases by (note that is a symmetric matrix). Mathematically,

To solve the key player problem, it suffices to prove that, for ,

And the key player is the player that maximizes .

To prove this, we take the following approach. Instead of removing node (and all its links with others), we reduce the weight of player from to , while keeping the weights of other players at as in the baseline model, i.e., for all . (It will be clear why we pick this particular .)

We claim that, after this reduction in weight, the resulting equilibrium is the same as the one when is removed from the network.

To see this, we first ask: what is the new equilibrium after this change in ? We claim that player would choose exactly zero action. This is because, by (5), the change in equilibrium action by player ,

is given by

from the construction of . Since initially player chooses , we have and the claim follows. What happens to other nodes? By (5), player ’s equilibrium action would change by , and the aggregate equilibrium action, by (6), would change by

This completes the proof of our claim. Thus, the key player in a network is the player who has the highest .

(3) For any group , we can define the inter-centrality measure

where , , is the submatrix of , that is, the matrix of the subnetwork formed by players in . Similarly, is a subvector of the unweighted Katz–Bonacich centrality vector for indices in the set . It can be shown that

where is the network obtained after removing all nodes and their links in . The proof is similar to the one in part (2), since removing from the network has the same effect on the equilibrium as changing the weight vector from to , while the weights of the nodes in the complement of remain fixed at as in the baseline model.

When is a pair with , we can explicitly express the index as follows:

The key pair is the pair with the largest .

We hope to receive your solutions to the proposed problems and your ideas on the open problems. Send your solutions to Michael Th. Rassias by email to mthrassias@yahoo.com.

We also solicit your new problems with their solutions for the next “Solved and unsolved problems” column, which will be devoted to Differential Equations.

- 1

This is the variance of the Bernoulli variable which takes a value of of a single individual drawn from the population is an altruist and otherwise, which is .

- 2

This result was first proved in a general evolutionary context by George R. Price [16 G. R. Price, Selection and covariance, Nature 227, 520–521 (1970) , 17 G. R. Price, Extension of covariance selection mathematics, Ann. Human Genetics 35, 485–490 (1972) ].

- 3

The literature on this model has further established the results that multiple periods of isolation in finite groups acts to amplify inter-group variance, so that even with random assortment into groups altruism can evolve [14 B. Cooper and C. Wallace, Group selection and the evolution of altruism. Oxford Economic Papers 56, 307–330 (2004) ]. It has also been found that use of punishment strategies in dynamic interactions can act to weaken this group selection mechanism [15 R. Povey, Punishment and the potency of group selection, J. Evolutionary Economics 24 (2014) ]. For an accessible book-length treatment of the topic of group selection in the biological and social sciences, see [18 E. Sober and D. S. Wilson, Unto Others, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1999) ].

- 4

That is, a point such that each .

- 5

For an overview of the literature on network games, see [20 M. O. Jackson and Y. Zenou, Games on networks. In Handbook of Game Theory. Vol. 4, edited by H. P. Young and S. Zamir, Handbooks in Economics, 91–157, Elsevier/North-Holland, Amsterdam (2015) ].

- 6

The key player problem has been introduced in [19 C. Ballester, A. Calvó-Armengol and Y. Zenou, Who’s who in networks. Wanted: the key player. Econometrica 74, 1403–1417 (2006) ].

- 7

For the analysis of group players, see [19 C. Ballester, A. Calvó-Armengol and Y. Zenou, Who’s who in networks. Wanted: the key player. Econometrica 74, 1403–1417 (2006) , 21 Y. Sun, W. Zhao and J. Zhou, Structural interventions in networks. arXiv:2101.12420 (2021) ].

References

- P. Biran, Symplectic packing in dimension 4. Geom. Funct. Anal. 7, 420–437 (1997)

- S.-F. Chiu, Nonsqueezing property of contact balls. Duke Math. J. 166, 605–655 (2017)

- Y. Eliashberg, S. S. Kim and L. Polterovich, Geometry of contact transformations and domains: orderability versus squeezing. Geom. Topol. 10, 1635–1747 (2006)

- A. Floer, H. Hofer and K. Wysocki, Applications of symplectic homology. I. Math. Z. 217, 577–606 (1994)

- M. Fraser, Contact non-squeezing at large scale in ℝ2n×S1. Internat. J. Math. 27, 1650107 (2016)

- M. Gromov, Pseudo holomorphic curves in symplectic manifolds. Invent. Math. 82, 307–347 (1985)

- D. McDuff and L. Polterovich, Symplectic packings and algebraic geometry. Invent. Math. 115, 405–434 (1994)

- F. Schlenk, Symplectic embedding problems, old and new. Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.) 55, 139–182 (2018)

- V. Conitzer, Eliciting single-peaked preferences using comparison queries. J. Artificial Intelligence Res. 35, 161–191 (2009)

- C. H. Coombs. Psychological scaling without a unit of measurement. Psychological Review 57, 145 (1950)

- E. Elkind, M. Lackner and D. Peters. Structured preferences. In Trends in Computational Social Choice, edited by U. Endriss, Chapter 10, AI Access, 187–207 (2017)

- H. Moulin, Axioms of Cooperative Decision Making. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1991)

- T. Walsh, Generating single peaked votes. arXiv:1503.02766 (2015)

- B. Cooper and C. Wallace, Group selection and the evolution of altruism. Oxford Economic Papers 56, 307–330 (2004)

- R. Povey, Punishment and the potency of group selection, J. Evolutionary Economics 24 (2014)

- G. R. Price, Selection and covariance, Nature 227, 520–521 (1970)

- G. R. Price, Extension of covariance selection mathematics, Ann. Human Genetics 35, 485–490 (1972)

- E. Sober and D. S. Wilson, Unto Others, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1999)

- C. Ballester, A. Calvó-Armengol and Y. Zenou, Who’s who in networks. Wanted: the key player. Econometrica 74, 1403–1417 (2006)

- M. O. Jackson and Y. Zenou, Games on networks. In Handbook of Game Theory. Vol. 4, edited by H. P. Young and S. Zamir, Handbooks in Economics, 91–157, Elsevier/North-Holland, Amsterdam (2015)

- Y. Sun, W. Zhao and J. Zhou, Structural interventions in networks. arXiv:2101.12420 (2021)

- S. Bikhchandani and J. W. Mamer, Competitive equilibrium in an exchange economy with indivisibilities. J. Econom. Theory 74, 385–413 (1997)

- S. Bikhchandani and J. M. Ostroy, The package assignment model. J. Econom. Theory 107, 377–406 (2002)

- N. Nisan, T. Roughgarden, É. Tardos and V. V. Vazirani, Algorithmic game theory. Cambridge University Press (2007)

Cite this article

Michael T. Rassias, Solved and unsolved problems. Eur. Math. Soc. Mag. 123 (2022), pp. 57–66

DOI 10.4171/MAG/78