Science has lost the greatest mathematician of the century […]; but I have lost my dearest friend (27 years of continuous, charming relations), who had always been extremely indulgent and kind to me! I have also lost the best and greatest supporter of a scientific organisation that I had created with so much effort. You know, moreover, that 15 of his most important memoirs were published in the Rendiconti [del Circolo Matematico di Palermo], among them that of 1894 (On the equations of mathematical physics), which is considered a classic, immortal work of this great genius. The first one (from 1888) was in the form of a letter addressed to me. And the last one… alas! was a farewell!

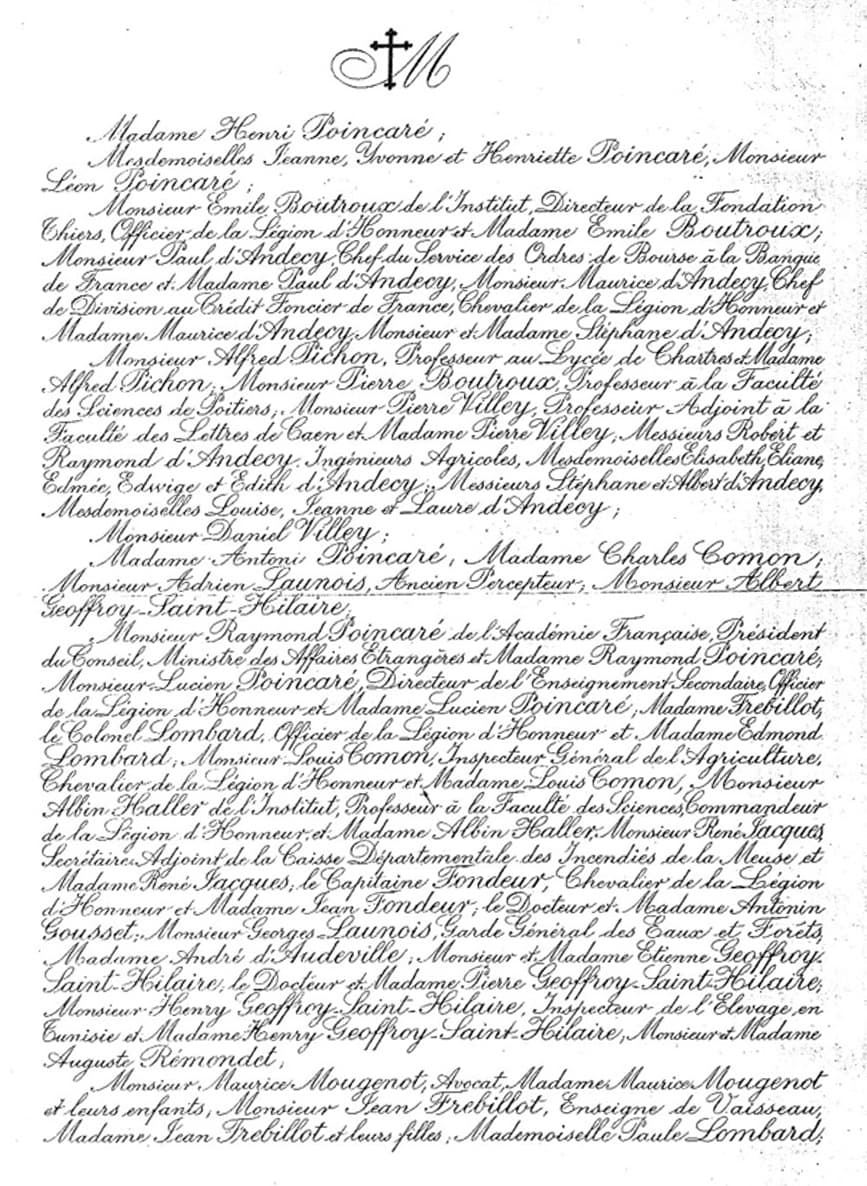

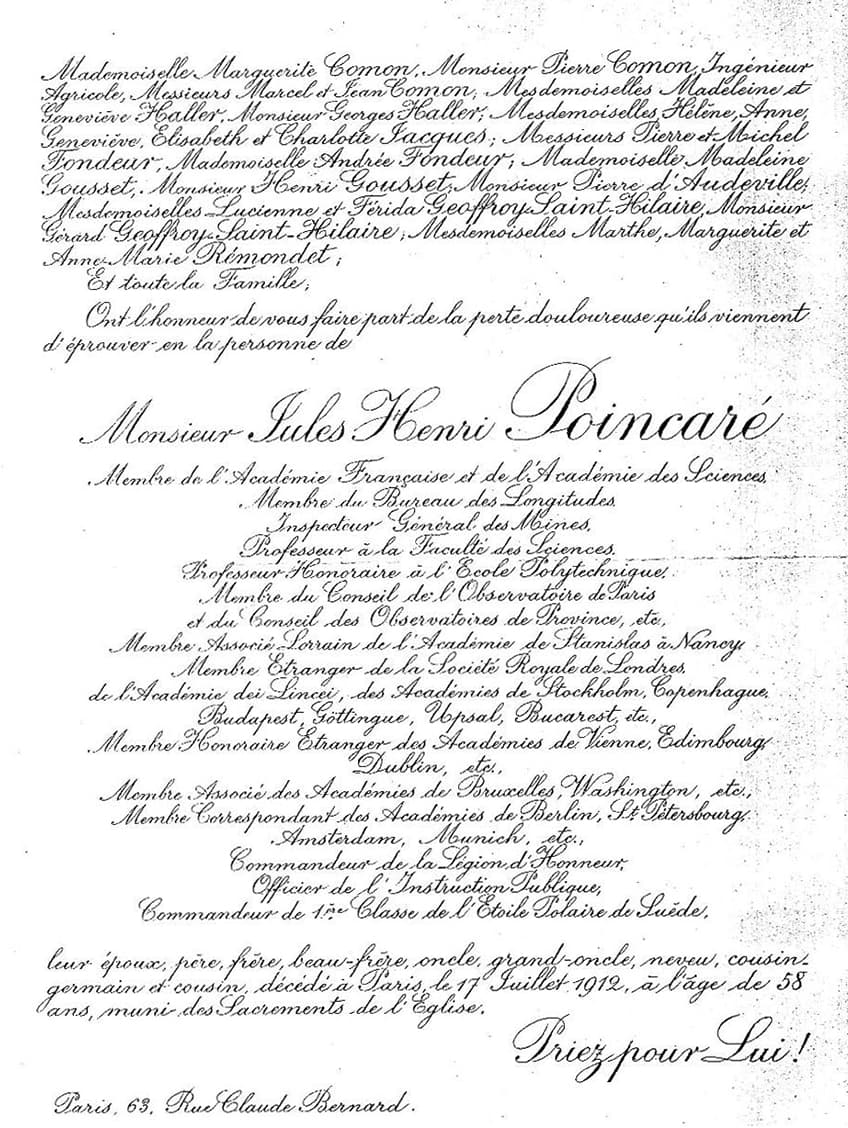

So said the mathematician Giovanni Battista Guccia (1855–1914) to Louise Poincaré, the mathematician’s widow, on 18 September 1912 [16 P. Nabonnand (ed.), Lettre de Giovanni Battista Guccia à Louise Poincaré, 18 septembre 1912. In [15] (to appear) ]. Henri Poincaré died on 17 July 1912 of an embolism following a bladder operation. He had clearly been declining for months, even going so far as to mention his ‘decrepitude’ in a letter to the mathematician Edgar Odell Lovett [28 S. Walter, P. Nabonnand, R. Krömer and M. Schiavon, Lettres d’Henri Poincaré à Edgar Odell Lovett, 28 mai 1912. In [27] (2016) ].

For weeks, the French and foreign press emphatically recalled the memory of the man who was a ‘poet of the infinite’ (Jules Clarétie), a ‘modest Titan’ (Ernest La Jeunesse) or the ‘consulting brain of human science’ (Paul Painlevé). These public sources follow a highly codified rhetoric, and their analysis allows us to observe the mechanisms involved in building Poincaré’s scientific and cultural heritage [22 L. Rollet, Les vies savantes d’Henri Poincaré (1854–1912). In Ce que la science fait à la vie, CTHS, Paris, 365–391 (2016) ]. The more intimate sources, such as letters of condolence, provide an overview of the family, friendship, social, scientific and professional networks in which Henri Poincaré was involved, as well as networks of scientific filiation.

All rights reserved.

The Archives Henri Poincaré in Nancy have been publishing Henri Poincaré’s scientific, administrative, and private correspondence for many years and are therefore mainly interested in the direct epistolary exchanges between the mathematician-philosopher and various correspondents.1The volumes published are devoted to correspondence between Poincaré and Gösta Mittag-Leffler [13 P. Nabonnand (ed.), La correspondance entre Henri Poincaré et Gösta Mittag-Leffler. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser, Basel (1999) ], correspondence with physicists [26 S. Walter, É. Bolmont and A. Coret (eds.), La correspondance entre Henri Poincaré et des physiciens, chimistes et ingénieurs. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser, Basel (2007) ], correspondence with astronomers, engineers and geodesists [27 S. Walter, P. Nabonnand, R. Krömer and M. Schiavon (eds.), La correspondance entre Henri Poincaré, les astronomes, et les géodésiens. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser, Basel (2016) ] and youthful correspondence [23 L. Rollet (ed.), La correspondance de jeunesse d’Henri Poincaré. Les années de formation. De l’École polytechnique à l’École des Mines (1873–1878). Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser, Basel (2017) ]. The forthcoming volumes are devoted to correspondence with mathematicians [15 P. Nabonnand (ed.), La correspondance entre Henri Poincaré et des mathématiciens. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser (to appear) ] and family, private and administrative correspondence [24 L. Rollet (ed.), La correspondance d’Henri Poincaré. Correspondance administrative, familiale et privée. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser (to appear) ]. This correspondence is gradually being put online at http://henripoincare.fr/s/accueil/page/accueil This undertaking sheds light on the development of his scientific work and opens biographical horizons that still need to be explored.2It is important to point out that the two most recent biographies of Poincaré published by Jeremy Gray [7 J. Gray, Henri Poincaré: A scientific biography. Princeton University Press, Princeton (2012) ] and Ferdinand Verhulst [25 F. Verhulst, Henri Poincaré: Impatient genius. Springer, New York (2012) ] only focus on his scientific work, leaving out part of his intimate, family, and personal life. In addition to these direct sources, there are indirect ones in which Poincaré’s personality and activity are mentioned, sometimes in a very meaningful way. The Archives possess a file of letters of condolence collected by his descendants from July to December 1912. They contain many clues about unsuspected networks of sociability and allow us to analyse the mechanisms involved in the early building of his posterity.

This article will present a first exploration of this largely unpublished corpus. It will be organised in three sections. The first part will briefly present the nature of this corpus and the authors of the letters it contains. Then a second part will give an overview of its content by concentrating on three subjects: firstly, the tributes and condolences, focusing on the most personal and less formal passages; secondly, the expressions of thanks sent by several mathematicians; and finally, the events organised in honour of Poincaré following his death.

1 Presentation of the corpus and the correspondents

After Poincaré’s death, his wife and some other family members kept a record of the expressions of sympathy they had received. This file was kept by the family’s descendants and has never been used until now; it was put in a folder labelled “1912. Letters of condolence kept after sorting. March 1955,” which seems to indicate that it was compiled in the wake of the celebrations of the centenary of Poincaré’s birth [3 Collectif, Le livre du centenaire de la naissance d’Henri Poincaré (1854–1954). Gauthier-Villars, Paris (1955) ].3The collection has been digitized by the Archives Henri Poincaré and all the letters will be published in volume 5 of the Poincaré correspondence [24 L. Rollet (ed.), La correspondance d’Henri Poincaré. Correspondance administrative, familiale et privée. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser (to appear) ]. This corpus contains a total of 38 letters: 32 were addressed to his wife Louise Poincaré (1857–1934) [21 L. Rollet, Jeanne Louise Poulain d’Andecy, épouse Poincaré (1857–1934). Bulletin de la Sabix 51, 18–27 (2012) ], two to his son Léon, two to his future son-in-law Léon Daum4Henri Poincaré and Louise Poulain d’Andecy had three daughters and one son. Jeanne Poincaré (1887–1975) married Léon Daum (1887–1966) in 1913. A graduate of the École Polytechnique, a mining engineer and heir to a family of Nancy crystal makers, he had a brilliant career as an industrial administrator and was even president of the European Coal and Steel Community from 1952 to 1953. Yvonne Poincaré (1889–1939) remained single and lived all her life at her mother’s side. Henriette Poincaré (1891–1970) married Edmond Burnier (1890–?) in 1921; the couple had four children and divorced in Annecy in 1955. Finally, Léon Poincaré followed in his father’s footsteps at the École Polytechnique (class of 1913), joined the engineering corps and ended his career as an Air Force engineer. He married Emma Motte in 1920 and had a child, François Poincaré (1920–2012). and two to the physicist Lucien Poincaré, the mathematician’s cousin and brother of Raymond Poincaré, the President of the French Republic.

The history of the building of this file is difficult to determine. It is conceivable that the family received much more than 38 letters of condolence after Poincaré’s death, so this collection probably represents only a portion of the letters received after 17 July 1912. Although small, its main interest lies in the fact that it allows us to discover new connections between Poincaré and other actors. And it turns out that many of the letters contained in this collection show correspondents for whom no trace of epistolary exchanges was available until now. The table below gives a broad overview of the authors of the letters along with biographical information.5In bold the names of correspondents for whom there are no known epistolary exchanges with Poincaré.

If we look at the places where the letters were sent from, we can see that a large proportion were sent from France (22 letters), with Germany in second place (5), followed by the United States (3), Japan (2) and Argentina (2). Such a geographical distribution is obviously not representative of the influence of Poincaré’s thought in 1912, but it opens new ways for thinking about the building of his posterity. It is worth mentioning that many correspondents listed here were trained, like Poincaré, at the École Polytechnique.

| Identity of correspondents | Place of dispatch of the letter | Brief biographical information |

| L. Barthélémy | Spincourt (France) | Partially illegible signature. It was probably a female cousin of Henri Poincaré’s mother, Eugénie (1830–1897). |

| Marie Bonaparte (1882–1962) | Paris (France) | She was the daughter of the geographer and patron Roland Bonaparte (1858–1924), Princess of Greece, a friend of Poincaré and the introducer of psychoanalysis in France. Poincaré was a regular visitor to her salon at the end of his life. |

| Élie Cartan (1869–1951) | Paris (France) | Mathematician, trained at the École Normale Supérieure. In 1912, he had just been appointed professor at the Sorbonne. |

| Clément Colson | Paris (France) | Poincaré’s classmate at the École Polytechnique, engineer, specialist in political economy and member of the French Conseil d’État. |

| Victor Crémieu (1872–1935) | Rodié (France) | French physicist trained at the Sorbonne. He had presented a doctoral dissertation under the supervision of Gabriel Lippmann [4 V. Crémieu, Recherches expérimentales sur l’électrodynamique des corps en mouvement. Gauthier-Villars, Paris (1901) ] and Poincaré was the author of the report on this dissertation. Crémieu’s work had been at the centre of a controversy concerning the interpretation of Henry Augustus Rowland’s experiment on the magnetic effects of a charged rotating disk. Poincaré had for a time sided with Crémieu against the interpretation of Harold Pender [8 L. Indorato and G. Masotto, Poincaré’s role in the Crémieu-Pender controversy over electric convection. Ann. of Sci. 46, 117–163 (1989) ]. This episode is documented by a correspondence between Poincaré and Crémieu [26 S. Walter, É. Bolmont and A. Coret (eds.), La correspondance entre Henri Poincaré et des physiciens, chimistes et ingénieurs. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser, Basel (2007) ]. |

| Maurice d’Ocagne (1862–1936) | Etretat (France) | Engineer and mathematician trained at the École Polytechnique (class of 1880). He is at the origin of an original method for the graphical solution of algebraic equations using scaled diagrams, called nomography. |

| Henri Deslandres (1853–1948) | Paris (France) | Engineer, military officer, and astronomer, trained at the École Polytechnique (class of 1872), where he probably met Poincaré for the first time. Deslandres was the director of the Meudon Observatory at the time of Poincaré’s death. Deslandres and Poincaré were members of the Bureau des Longitudes. |

| Jane Dieulafoy (1851–1916) | Montgiscard (France) | Archaeologist, novelist, journalist, and photographer. She was the wife of Marcel Dieulafoy (1844–1920), a mining engineer trained at the École Polytechnique (class of 1863) and at the École des Mines de Paris. He became a well-known archaeologist and a member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres. The tone of the letter reveals a certain closeness with the Poincaré family. |

| The director or a teacher at the École alsacienne | Paris (France) | Illegible signature. He wrote a letter of comfort to Poincaré’s son, Léon, which suggests that Léon had done part of his secondary education at that school. |

| Francis Foullioux | Égletons-les-Roses (France) | A Bachelor of Science, who declares himself to be a “modest pupil of the late Master”. |

| Tsuruichi Hayashi (1873–1935) | Sendai (Japan) | Professor of mathematics at Tōhoku Imperial University in Sendai, founder in 1911 of the Tôhoku Mathematical Journal [9 H. Kümmerle, Hayashi Tsuruichi and the success of the Tôhoku Mathematical Journal as a publication. In Mathematics of Takebe Katahiro and history of mathematics in East Asia, Adv. Stud. Pure Math. 79, Math. Soc. Japan, Tokyo, 347–358 (2018) ] and translator of the Japanese edition of Science and Hypothesis in 1909. |

| Felix Klein (1849–1925) | Hahnenklee (Germany) | Mathematician, professor at the University of Göttingen. |

| Johann Robert Lenz | Paris (France) | Lenz was probably a woodcarver who held the position of administrator-treasurer of the Université populaire du Faubourg Saint-Antoine in Paris. This institution published a journal, Les cahiers de l’Université populaire. Its editor was the anarchist sociologist Henri Dagan (1870–1912). Poincaré, who figured, like his two cousins Raymond and Lucien, among the subscribers of this journal, had given at least two lectures within this institution, one on chance and one on wireless telegraphy. |

| Max Lenz (1850–1932) | Berlin (Germany) | Historian, rector of the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Berlin. |

| Xavier Léon | Combault-Pontault (France) | Philosopher, founder of the Revue de métaphysique et de morale and of the Société française de philosophie. Poincaré was asked, along with Henri Bergson and Émile Boutroux, his brother-in-law, to be one of the leading authors for the launch of the journal in 1893. During his career, Poincaré published about twenty articles in this journal. He was also a member of the Société française de philosophie. Xavier Leon’s family was close to Poincaré’s; they met during summer holidays at Houlgate in Normandy. This relationship is documented by a fairly long correspondence [24 L. Rollet (ed.), La correspondance d’Henri Poincaré. Correspondance administrative, familiale et privée. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser (to appear) ]. |

| Paul Lévy (1886–1971) | Paris (France) | Mathematician, trained at the École Polytechnique (class of 1904). On 24 November 1911, he had presented a doctoral dissertation on integro-differential equations defining line functions before a jury composed of Émile Picard, Jacques Hadamard and Henri Poincaré (Poincaré wrote the report on the dissertation). |

| Edgar Odell Lovett (1871–1957) | Houston (United States) | American mathematician, founder and first president of the Rice Institute of Houston. He had invited Poincaré to participate in the inauguration of this institution in 1912 – without success, due to Poincaré’s precarious state of health. |

| Juraj Majcen (1875–1924) | Zagreb (Croatia) | Croatian mathematician, professor at the University of Zagreb |

| Camilo Meyer (1854–1918) | Buenos Aires (Argentina) | Mathematician and physicist born in Verdun. Meyer emigrated to Argentina in 1895 where he became a professor of mathematical physics at the University of Buenos Aires. Meyer was also a close childhood friend of Poincaré. |

| P. Millon | Sauvagnat (France) | Millon seemed close to the anthropologist and sociologist Gustave Le Bon (1841–1931). Le Bon was the director of the book collection Bibliothèque de Philosophie Scientifique published by Flammarion; it was on his initiative that Poincaré had published in this collection his well-known philosophical books, such as La Science et l’Hypothèse. Poincaré was quite close to Le Bon and regularly participated in the social dinners he organized. |

| Hantarō Nagaoka (1865–1950) | Tokyo (Japan) | Professor of physics at the University of Tokyo. He had participated in the first International Congress of Physics in Paris in 1900. |

| Heike Kammerlingh Onnes (1853–1926) | Leiden (Netherlands) | Professor of experimental physics at Leiden University. |

| Max Planck (1858–1947) | Berlin (Germany) | Professor of physics at the University of Berlin. |

| Henri Salomon (1861–?) | Paris (France) | Teacher of history and geography of Poincaré’s son, Léon, at the Lycée Henri IV in Paris. |

| Ludwig Schlesinger (1864–1933) | Giessen (Germany) | German mathematician, professor at the University of Giessen. |

| S. Frankfurter | Vienna (Austria) | The letter mentions a meeting in Vienna with Poincaré. One of Poincaré’s last trips abroad seems to have taken place in Vienna in May 1912, on the occasion of a celebration of the Friends of the Gymnasium. |

| Ernest Vessiot (1865–1952) | Paris (France) | Mathematician trained at the École Normale Supérieure. In 1912 he was a lecturer at the Sorbonne. He was also an examinateur d’admission at the École Polytechnique where his student was Poincaré’s son, Léon. The latter would enter the École Polytechnique in 1913. |

| Victorine | Nancy (France) | No last name. The deferential tone suggests that it may have been an employee who had been in the service of the Poincaré family in Nancy. |

| Jean Vassilas-Vitalis | Athens (Greece) | Professor at the Military School of Athens. He was a member of the Société mathématique de France since 1899. |

| Alexander Wilkens (1881–1968) | Kiel (Germany) | Astronomer at the Kiel Observatory in 1912. He later became director of the Breslau Observatory and then of the Munich Observatory. |

| Emily Wilson, born Newcomb (1869–1948) | New York (United States) | Daughter of the mathematician Simon Newcomb (1835–1909), a correspondent of Henri Poincaré. Emily Wilson was both a psychologist and a photographer. She was the wife of Francis Asbury Wilson (1861–1943), an illustrator who worked on advertisements for the R. J. Reynolds tobacco company. She seemed close to the Poincaré family, which she had obviously met at the Congress of Mathematicians in Rome in 1908, when Poincaré had fallen seriously ill. |

| Paul Xardel (1854–1933) | Rupt-sur-Moselle (France) | Childhood friend of Poincaré – his father was a colleague of Poincaré’s father at the Faculty of Medicine of Nancy –, a military officer trained at the Military School of Saint-Cyr. In 1912 he was a colonel in the infantry. We owe him an autobiographical testimony long remained unpublished on his friendship with Poincaré [29 P. Xardel, J’avais un ami … Henri Poincaré. In Vingt ans de ma vie, simple vérité … La jeunesse d’Henri Poincaré racontée par sa sœur (1854–1878), Hermann, Paris, 317–327 (2012) ]. |

2 An overview of the corpus

2.1 Tributes and condolences

On 18 July, an unidentified teacher from the Écolealsacienne6The Écolealsacienne was founded in Paris after the Franco–Prussian War of 1870. It was a renowned private institution. It still exists today. wrote to Poincaré’s son, Léon, to offer his condolences. Léon had obviously done part of his studies there before joining the special mathematics class at the Lycée Henri IV. He wrote to him: “I pity you with all my heart and would like to be able to tell you so in person. Keep alive in your soul the memory of the great scholar, the man of such integrity that was your father: he will hover over your existence, beneficent, comforting.” The mathematician Ernest Vessiot showed the same concern for Léon Poincaré in August by writing to his mother. After expressing his sorrow at the death of the man who had become his colleague after his appointment to the Sorbonne in 1910, he was careful to let her know that he was ready to postpone the examinations her son had to take as part of the entrance exam to the École Polytechnique.

Other personal testimonies are addressed to the family by voices close to Poincaré. Thus Paul Xardel, his childhood friend, wrote to Louise Poincaré on 18 July: “If I were not so far from Paris, I would have liked to join Henri’s friends and admirers tomorrow, who will come in droves to attest to the greatness of the loss you have just suffered, you and your children and with you France and the Universe. I am perhaps the oldest of his friends and, among his oldest admirers, who have always proclaimed his genius and predicted his glory. His genius will be celebrated by his followers and his pupils, and his glory is immortal. I would have liked piously to praise his heart, his loyalty to the friends of his childhood and youth, and I would have mourned with you the one you understood and helped so well.” Likewise, Marie Bonaparte, who wrote in July: “He was – as you know better than anyone – not only the greatest thinker, the most powerful genius of our time – but also a deep and incomparable heart; and having been close to him remains the precious memory of a whole life.”

The same testimony comes from Jane Dieulafoy, who apparently was an intimate of the family: “For me, I will always have the memory of the great mind who seemed to know and understand everything, even the secret of being kind and attentive to the thoughts of those who, compared with him, were only ignorant and puny.” (21 July). Or this testimony from a cousin from Poincaré’s maternal branch, Madame Barthélémy, who prays for the salvation of his soul: “I pray for you with all my heart, as well as for this beautiful soul. Perhaps, however, it hardly needs it. It seems to me that God must have received him as his child and that Henri is now in infinite happiness, knowing everything, understanding everything, immersed in beauty, in the eternal and shadowless goodness to which we ourselves will perhaps go one day.” (22 November 1912).

Perhaps just as moving, Francis Fouillioux, a Bachelor of Science and former student of the “Master,” wrote to his widow: “I am only a humble student, a modest pupil of the late Master whom you mourn. I mourned him with you because he was for me the personified glorification of human intelligence. He loved Science and was a philosopher: I owe him the best and greatest joys that a miserable life has allowed me to know.” (undated).

On the side of the scientists, the tributes are just as poignant, sometimes tinged with shyness. This is the case of the physicist Victor Crémieu, a student of Poincaré, who did not dare to write to his widow and sent his condolences to another member of the family, perhaps Lucien Poincaré. He evoked the almost filial relationship he had with him, remembering his doctoral dissertation and the scientific controversy that pitted him against Harold Pender: “It is only this morning that I learnt the distressing news of the death of the man I call my scientific father, and for whom I have always had feelings of filial affection. Intellectually I owe him everything, and morally a lot. It is simply out of discretion that since I have been living in the country, I stopped keeping in touch with him.” (20 July).

The next day, the astronomer Henri Deslandres wrote to Louise Poincaré and painted a scientific and moral portrait of the man he had worked with at the Bureau des Longitudes for many years: “Your husband was exceptional in terms of both his moral and scientific values. He was truly good and an honest man, in the broadest sense of the word; he inspired admiration, esteem and affection in all those who approached him. I had him as a neighbour for ten years at the Bureau des Longitudes, and I was able to appreciate him well. When a scientific difficulty arose, it was always to him that one turned, and if the solution was possible, he gave it at once. In matters of elections, he knew how to rise above party or chapel interests, and his opinion and his vote were dictated by justice alone or by a broad spirit of conciliation.”

Other scientists evoked the memory of their meeting with Poincaré at various events. For example, the Dutch physicist Heike Kammerlingh Onnes, referring to the great Solvay Congress of 1911 in Brussels: “I will never forget the great honour I had to sit next to Mr Poincaré at the Brussels Council. Who would have thought then that we would so soon experience the loss of his genius. The kindness that the great scientist showed me with his well-known gentleness will remain a beautiful memory for the rest of my life.” (27 August). Max Planck, who also attended the congress, recalled his meeting with Poincaré and his daughter (probably Jeanne Poincaré): “Although your husband was known and familiar to me for years in his wisdom, it was only last autumn in Brussels, when I had the honour of making his and your daughter’s personal acquaintance, that I had an idea of what you, dearest Madam, have lost in him. He did not work for time, but for eternity, and he lives on in the memory of all those who had the good fortune to approach him.”

Max Lenz, historian and rector of the University of Berlin, recalled Poincaré’s lecture on new mechanics in October 1910 at the institution’s centenary celebrations [18 H. Poincaré, La mécanique nouvelle. In Sechs Vorträge über ausgewählte Gegenstände aus der reinen Mathematik und mathematischen Physik, B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 49–58 (1910) ]: “It touches me all the more painfully today, on behalf of my colleagues, Madam, to have to express our deep participation in the indescribably great loss that you personally have suffered […]. His name, which will last as long as the theorems with which he enriched the mathematical sciences, will always find a place of veneration at the University of Berlin.”

Finally, in a long letter dated 9 August, the mathematician Felix Klein evoked the memory of his one-time rival in the 1880s over the naming of Fuchsian functions:

Please count me among those who are most directly affected by the death of your husband and who best understand how much science and his family have lost in him. It is more than thirty years since I encountered your husband and witnessed, so to speak, from week to week, the rise of his mathematical genius. As for me, I quickly collapsed under the weight of the work I had to do and was never able to reach the level of productivity I used to have. He, on the other hand, went from triumph to triumph, working out in a fast and victorious race what the rest of us considered a distant goal, namely full validity in the field of applications in addition to all the achievements in the field of pure mathematics. It is now an abrupt end! I do not know how long your husband suffered, but I have read and re-read with pensive interest the words with which he begins his last publication in the Rendiconti di Palermo. The rest of us also have enough reason to reflect on the passage of time.7In this article, devoted to “A new theorem of geometry” linked to the periodic solutions of the three-body problem, Poincaré wrote: “I have never presented to the public such an unfinished work; I therefore believe it necessary to explain in a few words the reasons which determined me to publish it, and first of all those which had engaged me to undertake it […]. It seems that under these conditions I should refrain from any publication until I have resolved the question; but after the useless efforts I have made over many months, it seemed to me that the wisest thing to do was to let the problem mature, resting on it for a few years; this would be very good if I were sure of being able to take it up again one day; but at my age I cannot answer for it.” [19 H. Poincaré, Sur un théorème de géométrie. Rend. Circ. Mat. Palermo 33, 375–407 (1912) , p. 375] I myself have had to take a leave of absence since New Year’s Day and I have been living here in a sanatorium ever since. The many unfinished projects that I have undertaken with others over the years have the advantage that I can devote myself to them in detail. Thus, the courses on the theory of automorphic functions, which I started 30 years ago with my brother on the icosahedron and which Rob. Fricke, from Braunschweig, and myself have recently completed have been published.8[6 R. Fricke and F. Klein, Vorlesungen über die Theorie der automorphen Functionen. Zweiter Band: Die functionentheoretischen Ausführungen und die Anwendungen mit 114 in den Text gedruckten Figuren. Teubner, Leipzig (1912) ] I assume that your husband received the delivery and that he was pleased to learn of the conclusion that our common field of work owes to the research of the younger generations.

2.2 Expressions of gratitude

Three letters – written by Maurice d’Ocagne, Élie Cartan and Paul Lévy – show the role played by Poincaré in supporting their careers. They were all addressed to Poincaré’s widow.

Maurice d’Ocagne, who was eight years younger than Poincaré, spoke, on 18 July, of his gratitude for the latter’s action in his favour when he was appointed professor of geometry at the École Polytechnique in 1912. He was also glad to have benefited from the mathematician’s support when he first applied for membership of the Académie des Sciences (although he was not elected until 1922). Poincaré and d’Ocagne had been in contact for several decades in various mathematical spheres, notably within the Société Mathématique de France and at the École Polytechnique, where d’Ocagne had been appointed as a répétiteur in 1893.

It was with a painful shock that I learned the awful news for which nothing had prepared me, and it was with a heart gripped by poignant emotion that I had the honour of addressing you a first telegram of condolences, regretting that distance did not allow me to express to you my feelings in person. For some thirty years I had the honour of enjoying the kindly friendship of your illustrious husband. There were so many occasions on which he gave me testimony of this that I cannot recall them all here. I will never forget the part he played in my appointment as a professor at the École Polytechnique, nor the encouragement he gave to my first attempt at becoming a candidate for the Institute. The fact that I received his vote on this occasion will remain one of the most precious honours of my scientific career. But what I want to remember most of all today is the cordial welcome I was always assured of from him and the camaraderie with which he tried to reduce the enormous intellectual distance between him and me.

On the same day, Élie Cartan, who had been from 1904 to 1909 professor of differential and integral calculus at the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Nancy [14 P. Nabonnand, Élie Cartan (1869–1951). In: Les enseignants de la Faculté des sciences de Nancy et de ses instituts. Dictionnaire biographique (1854–1918). Pun-Éditions Universitaires de Lorraine, Nancy, 159–162 (2016) ] and then lecturer at the Sorbonne until 1912, claimed to owe his appointment to a professorship to Poincaré’s benevolence:

To the general consternation produced by the news of Henri Poincaré’s death, to the grief felt by those who had the privilege of seeing and approaching the master, is added for me a more poignant pain. Perhaps the last act of his life as a professor and scholar was to come to the Sorbonne to read for me the report he had just made on my work. We will take pride, my family and I, in never forgetting him. It is my bitter regret to think that I will never be able to express my gratitude to him. The thanks that I could not give him, allow me, Madam, to give it to you and to your children.

Finally, on 9 August, the mathematician Paul Lévy recalled Poincaré’s warm welcome when he submitted his doctoral dissertation to him in 1911 [10 P. Lévy, Sur les équations intégro-différentielles définissant des fonctions de lignes. Gauthier-Villars, Paris (1911) ], even going so far as to advise him to defend it earlier than he had hoped. Lévy’s family was in acquaintance with Poincaré’s since the time when Levy’s father, Lucien, was a colleague of Poincaré at the École Polytechnique.

On learning of the loss that French science had just suffered in the person of Monsieur Poincaré, I did not dare at first to write to you to tell you how much I was sharing in your grief. The number of those who knew and admired the great scientist who has just passed away is so great that it seemed to me that they could not all let you know individually how much this misfortune affected them. However, I had reason to tell you how grateful I was to Monsieur Poincaré. More than a year ago, I came to him with a thesis that I asked him to read, and I will never forget how kindly he received me. He immediately started reading this work, and it is to him that I owe the fact that I was able to defend my thesis much earlier than I had hoped, and I also owe him advice which was invaluable for the future and whose significance I appreciate more and more. It was on receiving the letter of announcement sent to me, and even more on seeing in your letter to my mother your sympathy on the occasion of the mourning which has just affected us in our turn by the loss of my father, Mr. Lucien Lévy,9Lucien Lévy (1854–1912) died on 2 August. Trained at the École Polytechnique (class of 1872), he had been in contact with Henri Poincaré, who was a member of the following class. For a while he was a professor of higher mathematics at the Lycée Henri IV, and then became head of the Collège Sainte-Barbe in Paris. In 1890 he was appointed as an examinateur d’admission at the École Polytechnique, a position he held until 1910. During the last two years of his life, he was to be an examinateur de sortie in mechanics [2 R. Bricard, Lucien Lévy. Nouv. Ann. de Math. 4, 355–363 (1913) ]. that I decided to offer you the expression of my very respectful sympathy.

2.3 Two commemorations and a missed opportunity

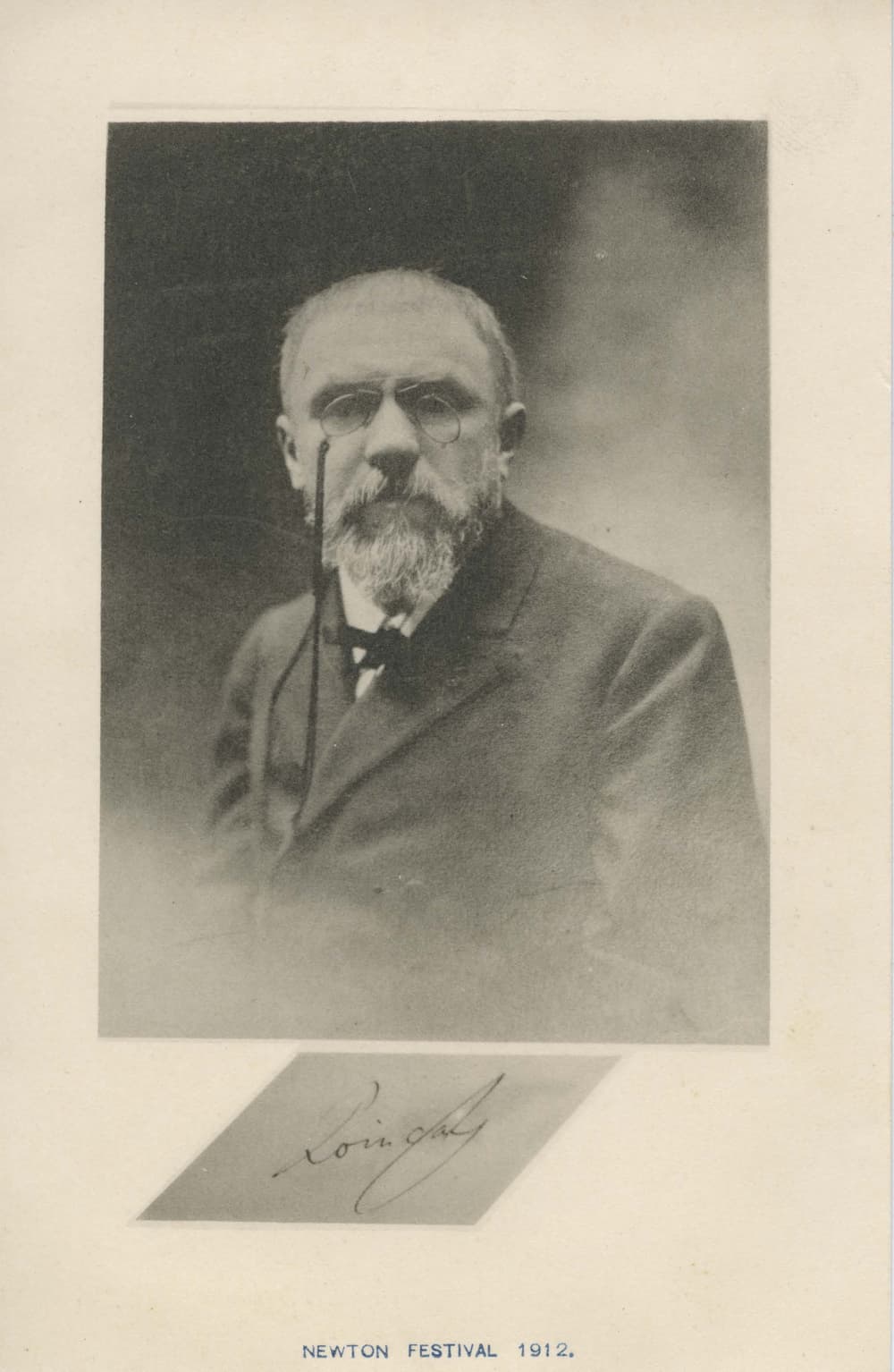

On 30 December 1912, the Japanese physicist Hantarō Nagaoka wrote to Henri Poincaré’s cousin Lucien. A physicist trained at the École Normale Supérieure, Lucien Poincaré was then Director of Higher Education at the Ministry of Public Instruction. In 1912, Nagaoka was at the Imperial University of Tokyo and he had received international recognition for his work on magnetostriction, earthquake wave propagation, electromagnetic wave transmission and, above all, atomic theory. In 1904, he had developed a planetary model of the atom based on an analogy with the planet Saturn, and some of his predictions had been confirmed by Ernest Rutherford in 1911. Nagaoka studied at the University of Tokyo and then in Europe, in Berlin, Munich and Vienna. He had participated in the first International Congress of Physics in Paris, during which he had undoubtedly been able to listen to and meet Lucien and Henri Poincaré. A theoretician and experimenter, he was also to become the first president of the Imperial University of Osaka and president of the Imperial Academy in 1939 [20 Publications de la Maison franco-japonaise (ed.), Hantarō Nagaoka (1865–1950). In Dictionnaire historique du Japon, Librairie Kinikuniya, Tokyo (1989) ].

All rights reserved.

In his letter to Lucien Poincaré, Nagaoka told him that the science students at the University of Tokyo had decided to organise a commemoration in Poincaré’s honour as part of an annual celebration, the Newton-Sai: “I have the pleasure of making you the following communication. The students in mathematics, astronomy and physics at the Tokyo Imperial University hold every year what they call Newton-Sai (literally translated, celebration in honour of Newton) on the birthday of Newton. The object of the assembly is simply to celebrate the deeds of great men in the domain of science, in which they are interested. This year they had to lament the death of your cousin, and they have prepared the endorsed postal card with the likeness of the illustrious dead for private circulation. It gives simple proof how he was admired and how his death was lamented in the Far East.” He enclosed the postcard that was distributed on that occasion.

Another example of a commemorative event appears in a correspondence between the Franco-Argentine physicist Camilo Meyer and Poincaré’s widow. Born in Verdun, Camilo Meyer was a childhood companion of Poincaré in Nancy [5 H. Damianovich and H. M. Levylier, Camilo Meyer, socio activo de la Sociedad cientifica argentina, 9 de Mayo de 1918. An. Soc. Cient. Argent. 86, 50–84 (1918) ]. Both had been pupils at the city’s high school and Meyer apparently came regularly to the Poincaré’s home. He was even a patient of Poincaré’s father, Émile Poincaré, who had a well-known medical practice in the city. After obtaining a degree from the Faculty of Science in Nancy, he apparently obtained a doctorate in Law. He moved to Argentina in 1895. Between 1910 and 1915 he taught a free course in mathematical physics at the University of Buenos Aires, based on the courses given by Poincaré at the Sorbonne. He was responsible for the first presentation of quantum theory in Argentina [12 C. Meyer, La radiación y la teoría de los quanta. Sociedad Científica Argentina, Buenos-Aires (1915) , 17 E. L. Ortiz, Julio Rey Pastor and the mathematical school of Argentina (in Spanish). Rev. Un. Mat. Argentina 52, 149–194 (2011) ]. The long letter he wrote to Louise Poincaré on 1 November 1912 gives an account of the action he took to honour the memory of his childhood friend by delivering, as early as 1 August 1912, a eulogy on the career and work of Poincaré at the Sociedad Científica Argentina of which he was an active member [11 C. Meyer, Henri Poincaré, An. Soc. Cient. Argent. 74, 125–147 (1912) ].

Madam, Although I am a stranger to you, I believe I am authorised by my long-standing relationship with the illustrious scientist, whom the intellectual universe has been mourning for three months, to send you a copy of the lecture which the Argentine Scientific Society requested of me as soon as the terrible news reached us. This homage, paid to the memory of the great scientist, was for me the fulfilment of a duty all the sweeter because, in seeking to revive the departed genius and to describe his gigantic work, I saw him again in my heart as I had always known him: an excellent comrade, modest, kind to everyone, and seeming to forget with each person the abyss that his unequalled genius opened up between his superhuman intelligence and the mind of ordinary mortals. I saw him again as a high-school companion, then as a fellow student, in those family gatherings at his home in rue de Serre in Nancy; I saw again his father the physician, my physician, also so kind, so helpful. These imperishable memories sustained me in the difficult task that was imposed on me, 3500 leagues away from Paris, only a few days after the telegraph had informed us of the catastrophe; although we were unaware of the details at the time, I was able, in a memorable meeting of the Scientific Society, in the midst of the general mourning of my colleagues, to condense in a talk all that I personally knew of the life and colossal work of my former comrade. I still do not know whether in other scientific centres similar ceremonies inspired by grief and admiration were organised with such promptness and ardour. In any case, I am proud to think that in this country, where I have lived for so many years, this unexpected death, which necessarily produced general consternation, was able to arouse an echo and provoke a demonstration of mourning for which I was the humble and unworthy spokesman. Would it be an abuse of your indulgence, Madam, to ask you timidly for the slightest souvenir of the man with whom I was already a close friend more than forty years ago? whom I followed step by step in his triumphal march, and whose works form the main element of my library? We were only a few days apart in age; despite a separation dating back a long time, I still had the resource of writing to him sometimes, and he always replied to me despite an overwhelming daily workload. You would not believe how happy I would be to possess any object, the most insignificant of all, which had belonged to him: it seems to me that I would thus find less bitter the few years left to me to live. Please excuse my boldness, which is great, and this long letter, and accept, Madam, my highest regards. C. Meyer Professor of Mathematical Physics at the Faculty of Sciences of Buenos Aires Calle Independencia 1241, November 1912

A third example of an epistolary exchange allows us to document precisely an episode at the end of Poincaré’s life. In 1912, he exchanged several letters with the American mathematician Edgar Odell Lovett. The latter wanted to invite him to give a lecture at the inauguration of the Rice Institute in Houston, which was to take place from 10 to 12 October 1912. Poincaré declined the invitation to travel because of his health and died in July. He had nevertheless promised to send the manuscript of an article to be published in the proceedings of this event. Consequently, Lovett wrote to Louise Poincaré on 4 September 1912 to ask if her husband had had time to write the manuscript before his death.

As you will recall, the Trustees of the Rice Institute had done themselves the honour of inviting your late distinguished husband, Professor Henri Poincaré, to lecture at the formal opening ceremonies to be held October tenth, eleventh, and twelfth. He feared that his health would not permit him to make the long journey to Houston, but expressed his willingness, on our repeating the invitation, to send us a manuscript in October for publication in the proceedings of our first academic festival. It has occurred to me that you may find such a manuscript among his papers. If this should be the case, we should be most happy to receive it. In this event we should of course expect to pay to the estate the honorarium which had been proposed.

Louise Poincaré replied to Lovett by saying that she had found no trace of any manuscript and that her husband was probably planning to write it during the summer holidays. Émile Borel, who had been Poincaré’s student and a close colleague, was part of the French delegation to the inauguration of the Rice Institute and gave a poignant account of his last exchanges with him on that occasion: “When Henri Poincaré was invited by President Edgar Odell Lovett to deliver an address at this scientific celebration, his acceptance was conditional on the state of his health. A few months later, he finally declined the invitation, promising, however, to send his lecture in writing. I cannot remember without emotion the last conversation I had with him on that subject. I was still hoping that his decision was not final; but, after giving me some friendly advice about my lectures and the journey, he told me with what deep regret he had to give up the thought of ever visiting the United States again, and I felt, for the first time, how serious was the condition which justified his refusal. A few weeks afterward he was gone.” [1 E. Borel, Molecular theories and mathematics. Rice Institute Pamphlet 1, 163–193 (1915) ]

3 Conclusion

As stated above, this corpus of carefully preserved letters makes it possible to discover new facets of Henri Poincaré’s relationships with family, friends, social and professional contacts. It also provides an opportunity to analyse the processes transforming his work into a heritage in France and abroad; in this respect, the episodes of commemoration in Argentina and Japan are particularly enlightening. Finally, and above all, these new or poorly documented networks of relations open interesting biographical perspectives insofar as they offer the possibility of discovering both actors who were important to Poincaré and others for whom Poincaré himself was important. Such a source makes it possible to re-discover a personality who was not only a mathematician and a scientist, but also a social actor and a leading intellectual.

- 1

The volumes published are devoted to correspondence between Poincaré and Gösta Mittag-Leffler [13 P. Nabonnand (ed.), La correspondance entre Henri Poincaré et Gösta Mittag-Leffler. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser, Basel (1999) ], correspondence with physicists [26 S. Walter, É. Bolmont and A. Coret (eds.), La correspondance entre Henri Poincaré et des physiciens, chimistes et ingénieurs. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser, Basel (2007) ], correspondence with astronomers, engineers and geodesists [27 S. Walter, P. Nabonnand, R. Krömer and M. Schiavon (eds.), La correspondance entre Henri Poincaré, les astronomes, et les géodésiens. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser, Basel (2016) ] and youthful correspondence [23 L. Rollet (ed.), La correspondance de jeunesse d’Henri Poincaré. Les années de formation. De l’École polytechnique à l’École des Mines (1873–1878). Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser, Basel (2017) ]. The forthcoming volumes are devoted to correspondence with mathematicians [15 P. Nabonnand (ed.), La correspondance entre Henri Poincaré et des mathématiciens. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser (to appear) ] and family, private and administrative correspondence [24 L. Rollet (ed.), La correspondance d’Henri Poincaré. Correspondance administrative, familiale et privée. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser (to appear) ]. This correspondence is gradually being put online at http://henripoincare.fr/s/accueil/page/accueil

- 2

It is important to point out that the two most recent biographies of Poincaré published by Jeremy Gray [7 J. Gray, Henri Poincaré: A scientific biography. Princeton University Press, Princeton (2012) ] and Ferdinand Verhulst [25 F. Verhulst, Henri Poincaré: Impatient genius. Springer, New York (2012) ] only focus on his scientific work, leaving out part of his intimate, family, and personal life.

- 3

The collection has been digitized by the Archives Henri Poincaré and all the letters will be published in volume 5 of the Poincaré correspondence [24 L. Rollet (ed.), La correspondance d’Henri Poincaré. Correspondance administrative, familiale et privée. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser (to appear) ].

- 4

Henri Poincaré and Louise Poulain d’Andecy had three daughters and one son. Jeanne Poincaré (1887–1975) married Léon Daum (1887–1966) in 1913. A graduate of the École Polytechnique, a mining engineer and heir to a family of Nancy crystal makers, he had a brilliant career as an industrial administrator and was even president of the European Coal and Steel Community from 1952 to 1953. Yvonne Poincaré (1889–1939) remained single and lived all her life at her mother’s side. Henriette Poincaré (1891–1970) married Edmond Burnier (1890–?) in 1921; the couple had four children and divorced in Annecy in 1955. Finally, Léon Poincaré followed in his father’s footsteps at the École Polytechnique (class of 1913), joined the engineering corps and ended his career as an Air Force engineer. He married Emma Motte in 1920 and had a child, François Poincaré (1920–2012).

- 5

In bold the names of correspondents for whom there are no known epistolary exchanges with Poincaré.

- 6

The Écolealsacienne was founded in Paris after the Franco–Prussian War of 1870. It was a renowned private institution. It still exists today.

- 7

In this article, devoted to “A new theorem of geometry” linked to the periodic solutions of the three-body problem, Poincaré wrote: “I have never presented to the public such an unfinished work; I therefore believe it necessary to explain in a few words the reasons which determined me to publish it, and first of all those which had engaged me to undertake it […]. It seems that under these conditions I should refrain from any publication until I have resolved the question; but after the useless efforts I have made over many months, it seemed to me that the wisest thing to do was to let the problem mature, resting on it for a few years; this would be very good if I were sure of being able to take it up again one day; but at my age I cannot answer for it.” [19 H. Poincaré, Sur un théorème de géométrie. Rend. Circ. Mat. Palermo 33, 375–407 (1912) , p. 375]

- 8

[6 R. Fricke and F. Klein, Vorlesungen über die Theorie der automorphen Functionen. Zweiter Band: Die functionentheoretischen Ausführungen und die Anwendungen mit 114 in den Text gedruckten Figuren. Teubner, Leipzig (1912) ]

- 9

Lucien Lévy (1854–1912) died on 2 August. Trained at the École Polytechnique (class of 1872), he had been in contact with Henri Poincaré, who was a member of the following class. For a while he was a professor of higher mathematics at the Lycée Henri IV, and then became head of the Collège Sainte-Barbe in Paris. In 1890 he was appointed as an examinateur d’admission at the École Polytechnique, a position he held until 1910. During the last two years of his life, he was to be an examinateur de sortie in mechanics [2 R. Bricard, Lucien Lévy. Nouv. Ann. de Math. 4, 355–363 (1913) ].

References

- E. Borel, Molecular theories and mathematics. Rice Institute Pamphlet 1, 163–193 (1915)

- R. Bricard, Lucien Lévy. Nouv. Ann. de Math. 4, 355–363 (1913)

- Collectif, Le livre du centenaire de la naissance d’Henri Poincaré (1854–1954). Gauthier-Villars, Paris (1955)

- V. Crémieu, Recherches expérimentales sur l’électrodynamique des corps en mouvement. Gauthier-Villars, Paris (1901)

- H. Damianovich and H. M. Levylier, Camilo Meyer, socio activo de la Sociedad cientifica argentina, 9 de Mayo de 1918. An. Soc. Cient. Argent. 86, 50–84 (1918)

- R. Fricke and F. Klein, Vorlesungen über die Theorie der automorphen Functionen. Zweiter Band: Die functionentheoretischen Ausführungen und die Anwendungen mit 114 in den Text gedruckten Figuren. Teubner, Leipzig (1912)

- J. Gray, Henri Poincaré: A scientific biography. Princeton University Press, Princeton (2012)

- L. Indorato and G. Masotto, Poincaré’s role in the Crémieu-Pender controversy over electric convection. Ann. of Sci. 46, 117–163 (1989)

- H. Kümmerle, Hayashi Tsuruichi and the success of the Tôhoku Mathematical Journal as a publication. In Mathematics of Takebe Katahiro and history of mathematics in East Asia, Adv. Stud. Pure Math. 79, Math. Soc. Japan, Tokyo, 347–358 (2018)

- P. Lévy, Sur les équations intégro-différentielles définissant des fonctions de lignes. Gauthier-Villars, Paris (1911)

- C. Meyer, Henri Poincaré, An. Soc. Cient. Argent. 74, 125–147 (1912)

- C. Meyer, La radiación y la teoría de los quanta. Sociedad Científica Argentina, Buenos-Aires (1915)

- P. Nabonnand (ed.), La correspondance entre Henri Poincaré et Gösta Mittag-Leffler. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser, Basel (1999)

- P. Nabonnand, Élie Cartan (1869–1951). In: Les enseignants de la Faculté des sciences de Nancy et de ses instituts. Dictionnaire biographique (1854–1918). Pun-Éditions Universitaires de Lorraine, Nancy, 159–162 (2016)

- P. Nabonnand (ed.), La correspondance entre Henri Poincaré et des mathématiciens. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser (to appear)

- P. Nabonnand (ed.), Lettre de Giovanni Battista Guccia à Louise Poincaré, 18 septembre 1912. In [15] (to appear)

- E. L. Ortiz, Julio Rey Pastor and the mathematical school of Argentina (in Spanish). Rev. Un. Mat. Argentina 52, 149–194 (2011)

- H. Poincaré, La mécanique nouvelle. In Sechs Vorträge über ausgewählte Gegenstände aus der reinen Mathematik und mathematischen Physik, B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 49–58 (1910)

- H. Poincaré, Sur un théorème de géométrie. Rend. Circ. Mat. Palermo 33, 375–407 (1912)

- Publications de la Maison franco-japonaise (ed.), Hantarō Nagaoka (1865–1950). In Dictionnaire historique du Japon, Librairie Kinikuniya, Tokyo (1989)

- L. Rollet, Jeanne Louise Poulain d’Andecy, épouse Poincaré (1857–1934). Bulletin de la Sabix 51, 18–27 (2012)

- L. Rollet, Les vies savantes d’Henri Poincaré (1854–1912). In Ce que la science fait à la vie, CTHS, Paris, 365–391 (2016)

- L. Rollet (ed.), La correspondance de jeunesse d’Henri Poincaré. Les années de formation. De l’École polytechnique à l’École des Mines (1873–1878). Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser, Basel (2017)

- L. Rollet (ed.), La correspondance d’Henri Poincaré. Correspondance administrative, familiale et privée. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser (to appear)

- F. Verhulst, Henri Poincaré: Impatient genius. Springer, New York (2012)

- S. Walter, É. Bolmont and A. Coret (eds.), La correspondance entre Henri Poincaré et des physiciens, chimistes et ingénieurs. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser, Basel (2007)

- S. Walter, P. Nabonnand, R. Krömer and M. Schiavon (eds.), La correspondance entre Henri Poincaré, les astronomes, et les géodésiens. Publ. Arch. Henri-Poincaré, Birkhäuser, Basel (2016)

- S. Walter, P. Nabonnand, R. Krömer and M. Schiavon, Lettres d’Henri Poincaré à Edgar Odell Lovett, 28 mai 1912. In [27] (2016)

- P. Xardel, J’avais un ami … Henri Poincaré. In Vingt ans de ma vie, simple vérité … La jeunesse d’Henri Poincaré racontée par sa sœur (1854–1878), Hermann, Paris, 317–327 (2012)

Cite this article

Laurent Rollet, “My sincere condolences”. Eur. Math. Soc. Mag. 128 (2023), pp. 41–50

DOI 10.4171/MAG/141